Vic, or Being Right

is the Wrongest Thing I Do

By Tom Baker

This article was first written in 1997 and was subsequently published in the Aquarius Memorial Issue in the fall of 2003.

"Almost, (a pause), almost everything you've ever been told is a lie."

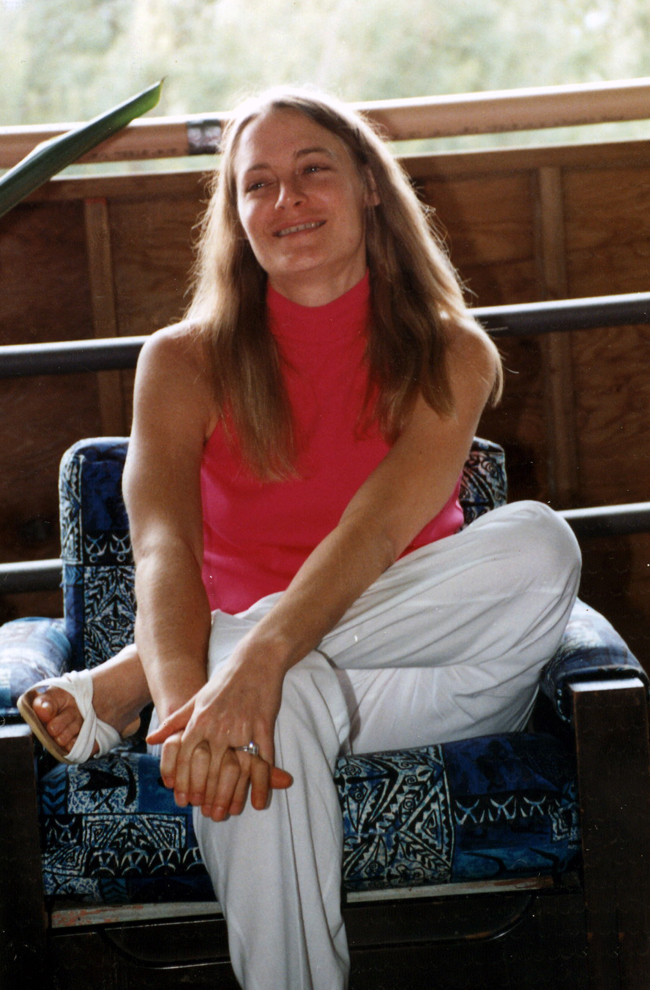

The delivery was flat and sure, like John Wayne in The High and the Mighty. It cut easily through the sound of the rain on the tin roof. Sally and I were on the North Shore of Oahu, perched on a sofa, trembling in the presence of Victor Baranco, the Magus of More University. He was the latest in our gallery of gurus and we had booked a five-day Audience so that we could get the "Vic experience" firsthand.

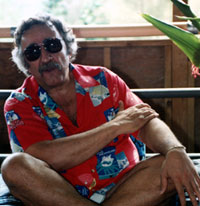

He wore a bed-sheet-sized red and blue Hawaiian shirt, and I remember thinking that we had traveled a long way from Deepak Chopra. The fire threw light onto his massive coffee-colored face; his eyes took in a lot more than they gave away. He was tired and hurting from a lifetime of abusing his body, and he looked like he didn't want his time wasted.

"What is true is that everything you've ever been told has been told to you for some other reason than the teller was interested in your knowing. That's everything. (Another pause.) That's everything."

The last emphasis was to make clear that he was including himself in the message, that he was about to mess with our minds — and that he could mess better than anyone in the business. One of his observations is about how men, as opposed to women, need an act of violence, or something very close to that, in order to change direction. The five-day Audience in Vic's living room was to be an act of violence for me.

I had first heard of Vic two years before. Sally and I had been getting advance press on him from the day we moved to Marin. Inevitably in a discussion about relationships, or sex, or what men and women really want, somebody would quote Vic and immediately raise the emotional level of the conversation. Everything he said, or was attributed to him, zapped into a nerve, especially my nerves. It seemed that Vic liked to frame his pronouncements-he preferred calling them "observations" — in the hardest possible way for me to hear them. This is his charm.

His specter grew when we started to take courses at Morehouse, formerly known as More University, which is an extant sixties-era commune located in a series of purple-painted buildings on a pretty piece of property in Lafayette, California, east of Berkeley. Vic was one of the founders of the commune some thirty years ago, helped finance it, and is its philosophical father. He and his cohorts do on-going extensive research, primarily into the area of women's pleasure, but also into sexuality in general, communication, communal living, and the like. And over the years Vic designed a number of courses, or seminars, so that they could share their research with anyone who had a few hundred bucks and the courage to go to a very strange-looking place and get into confrontational conversations with some really scary people.

From the first course we took at More, the teachers would invariably invoke Vic. "Well, Vic says," and then they would look carefully at their notes to make sure they told us exactly what he had said. One got the impression that Vic didn't much like to be misquoted. During a break, they would often call him in Hawaii to pose a particular question, and after the break his reply would be read. (Vic and his wife, Cindy had moved to Oahu, along with a dozen or so of their communal buddies, to recover from various medical problems, but they keep a close eye on what's happening at Lafayette.)

The odd thing about his replies was that they never sounded like he was responding to the question you asked. They didn't even sound like he was responding to the right person. You always felt like you were getting somebody else's mail. Then, about a half-hour later, you felt a little disoriented, like your inner ear wasn't functioning properly, and then, in a day or two, your life changed.

The year before, Sally and I had been taking a course called "Man/Woman," a seminar designed to help you look at the mechanisms of relationship in a different way. Since we had already taken a few courses at More, we knew to expect the kind of emotional land mines that Vic and gang enjoy setting for you. The leaders were JAM, which stands for Jackie, Alec, and Marilyn, who have thirty or so years of experience, both in living communally at More and at teaching the word of Vic. Marilyn, the most verbal of the three, can't say enough about Vic.

"No one ever saw me the way Vic does," she says, or she tells a story about how Vic can bring her to orgasms from the North Shore of Oahu without even lifting the telephone.

That's another thing about Vic's advance press: that he has utter confidence in his ability to give pleasure to a woman, any woman; that he knows more about women's pleasure than anyone of either sex. And the teachers at More and all the other people who have known him through the years just nod and agree: "yep, he does" and that's that.

Knowing how Vic and gang prefer to carve up real people in their seminars rather than talk in the abstract, Sally and I brought to the Man/Woman course a problem that had come up for us and had caused some tension. Typically, it had something to do with work. If you ever want to cut through the veneer of our beautifully polished relationship, just offer one of us a job and leave the other unemployed. Cracks appear immediately. It's been that way for nearly thirty years. The story we told them is that I had been offered a job, a TV movie in Vancouver. Since it was only a few days shooting over a period of a couple of weeks and they would agree to pay for the plane trips back and forth, I accepted immediately. Neither of us had been taking any work for a while and we could certainly use the income, so it seemed like a no-brainer to me. Minimum time away, nice money, what's the problem? Sally was in complete agreement. Being a little guilty anyway for turning down some big bucks a couple of months before, she hugged me and told me she knew that I needed this, both for the money and the taste of an acting experience again, and she gave me her radiant blessing. Off I went to Vancouver, worked for two days, and came home to find our relationship in total breakdown. Well, not total, but definitely not the harmony-bordering-on-bliss that we had grown accustomed to. What'd happened? Where had we gone wrong?

JAM phoned the question in to Hawaii, not to Vic, who doesn't speak on the phone, but to Maxine, who relays the question verbatim to Vic, who ponders it and then dictates a reply back to Maxine, who repeats it as clearly as she can by phone to JAM, who read it to us as the rest of the class looks on. "He," reads Marilyn, pointing at me — "is an arrogant asshole. And she," looking at Sally now, "is a liar."

This was my first direct communication from the very mouth of Vic, and my immediate reaction was to gather my beloved and escort her out of this strange place and back to Marin where people are civil and reside one family to a house with their dogs and their kids, when I noticed that Sally was nodding in agreement. Was she agreeing, I wondered, that she was a liar or that I was an asshole? I decided to stay frozen to my seat and wait, which is what I usually do in moments of great fear. Vic's message went on. I was arrogant because I had decided unilaterally on our future. I had made the decision as the leader, the one who understands monetary things, the man. And Sally had lied when she agreed that I knew what was best for both of us. Vic pointed out that Sally's phrase, "You need this, honey" can be directly translated as, "I don't want this."

"Wait a minute," I tried to be calm. "Last summer, she turned down a movie that would have floated us for six months. She made the decision, which was okay with me because it was her movie. What's wrong with my deciding what I want to do with my movie?"

"You're saying you think this should be an equal situation," said Alec. "What's right for her is right for you."

"Exactly."

"Forget it. There's no equality between men and women. There never has been. The only reason you never noticed it before is that it always came down in your favor."

That stopped me for a second, but only for a second. "So you're saying that she can do whatever she wants with her career, but I have to run all my decisions through her?" "Only if you want to be happy," said Marilyn with a smile. Every muscle in my body seized up. My ego screamed "Mayday!" and looked around frantically for support. This information absolutely could not be correct. Then Sally asked them, "How, according to Vic, should we have played this?"

Jackie spoke to me, "First of all, when the call came in, you could have said that you had to talk to Sally before you gave them an answer."

"Okay." That wasn't too hard to swallow.

"Because if you speak first, especially with that 'I know what's best for us, dear' tone in your voice, there's no way you'll ever hear what she wants. She won't even be able to say it to herself."

Then she asked Sally how she would have responded if I hadn't preempted her. Sally thought it over and said that she probably would have asked me to stay home. She'd gotten fond of having me around.

"That's because she has complete disdain for money!" I screamed. "She's only happy when she works for nothing!"

"So after you heard Sally's position, that she'd rather have you at home than away making money, then what would you have said?"

"I would have pointed out that we haven't taken anything in for the last six months and that somebody has got to be responsible for the security of our family."

"Are you out of money?"

"We will be if we keep going like this. All we do is take seminars."

"But you're not out of money now?"

I didn't dignify that with a reply.

"We have tons of money," piped in Sally, supportively.

I hit the ceiling. "Sure, we have money. We have it because I made goddamn sure that everything's been taken care of. The only reason she can be so blasé is that I worry my heart out about money every night of my life!"

Then Jackie turned to me, "If she had sat down with you and taken a good hard look at the bank balances and all the bills coming in, and convinced you that she understood your financial situation perfectly, and then told you that she'd rather have you at home right now anyway, then what would you have said?"

"You mean …?"

"I mean that she acknowledges how wonderfully you've taken care of her, how safe you've made her and your children, and that right now it's more important that she has you at home putting all your attention on her, and that when the time comes that she's worried about her security, she'll send you back out to work. And trust me, she will."

"You mean that …?"

"I mean that if you went away, the thing that would be missing for her is you, which might be more important right now than stockpiling the bank account."

That got my attention. But I still wasn't ready to be wrong about this.

"This is not just about my bank account. It's also about my need to be an artist, my creativity."

This was bullshit, because this particular job had nothing to do with anybody being an artist. It was a dumb TV movie starring the producer's daughter. But I was grasping at straws.

"Maybe she wants you to show her that she's more important than your creativity. Maybe she wants you to admit that she's the source of it."

Something started to quiver inside me, something I thought was so set in cement that it would need a nuclear device to shake it from its moorings. It didn't crumble then, but it started to vibrate a little, vibrate with the fear that everything I ever thought about loving Sally was wrong. And if that was wrong, I was lost as to where I was. Essentially, the change they were asking me to consider was from caring for Sally in the way I thought was best for her, to caring for Sally in the way she thought was best for her. This is one big-ass change.

"Women don't want to fuck."

This was Brian Shekeloff, another of the teachers at More, speaking. He was relating to us a discussion he had had with Vic a few years earlier. Vic had been explaining to him why women don't think of sex as being for their pleasure.

"Well," answered Brian to Vic, "some women like to fuck."

Vic shook his head. "Let's say you got arrested and thrown in jail — real jail, not some country club. And there were all these large, really bad men who looked at you as the newest piece of ass on the block. What do you do?"

Brian joked a few times, tried to squirm out of the question, but Vic held him to it.

"What's the best deal you can make?"

"I guess I'd find the biggest, scariest one and cultivate a relationship with him. I'd try to be 'his' and get him to protect me from all the others."

"And then what?" asked Vic.

"Then I'd fuck him as little as possible," said Brian, laughing.

"That's marriage," said Vic. "That's the deal women make every day."

This was in our first course at More. Brian and Kassy were the leaders. Brian has been around since Vic's Berkeley days and serves as Buckingham to Vic's Richard the Third. He's exceptionally bright and a great storyteller. Kassy, his wife, is easily a match for him. She has solidity and assurance and a wicked sense of humor. They both were living in Hawaii with Vic and had come to California to lead a course called "A Prerequisite for Vic". The idea being that Vic was coming in a month or two and would hold courses only for people who had been instructed in the art of not wasting his time. Brian and Kassy were very good at this kind of instruction.

Everything they said was in answer to a question. And when there were no questions, we all sat in an uncomfortable silence until there was one.

"How can I get him to listen to me?" asked one woman about her husband. "I've tried everything to get his attention, but nothing I do seems to work."

"Take a two-by-four," suggested Kassy helpfully, "and smack him in the head with it. See if that doesn't get his attention."

Kassy was actually responsible for my first bolt from the blue in a More course. She was going on about how women were multi-functional and multi-directional, whereas men were better at doing one function, in one direction, until it was done. She was saying how women had "call" and men only had "response to call". She said that a man who used a woman for his juice could live in Technicolor while a man drawing on his own inspiration was relegated to a black-and-white life on an eight-inch screen. I wasn't buying it.

"Maybe I'm a woman," I offered hopefully, "but I was the one responsible for our most recent change in direction. I came up with the idea of moving out of L.A.; I was the one who went out on a limb and said we could live anywhere as long as we loved each other. I was …"

"And you think all that was your idea?" asked Kassy, cocking an eyebrow.

And like a golf ball smacking me in the forehead, I knew she was right. If Sally had wanted to stay in L.A. and do more television, I would have been blithely pursuing another TV series, semiconsciously playing golf four days a week, not even for a second thinking about moving away from what was a cushy, ego-inflating life. But the woman I was in love with didn't want that life. My woman wanted something else. She didn't know exactly what it was, and even if she did, she had lived too long in a male-dominated culture to dare ask for it. But she did let me know, in her subtle but unsubtle way, that we weren't in pursuit of the life that would take her to bliss, and would I please rectify that as soon as possible. So I did just that — of course, instantly restructuring the entire thing to be perceived as my idea so that my ego could be comfortable with it. That's what happened back in L.A. That's actually the way it came down. And it took Kassy with the sarcastic smirk on her face to make me see it.

The lore that has been spun around Vic Baranco is prodigious. And most, if not all, of it stems from things he said about himself. One story tells about how his parents had him tested at three years old because it was clear they had a genius on their hands and by the age of five he had cracked the code of the Stanford-Benet IQ test and churned out perfect 200's whenever he took it. After college at Berkeley, he became a dealer in distressed merchandise and made and lost a number of fortunes. He ran the "biggest show club in San Francisco". He was a gigolo, turning tricks for money. He was a bouncer. He mastered the art of jaw breaking. He and his wife Susie joined the sexual revolution in the sixties. They and their colleagues undertook "the most extensive research into women's pleasure that has ever been conducted."

In one seminar held at a local Ramada Inn, in which Vic and his current wife Cindy were demonstrating a woman in continuous orgasm for three hours, as the audience passed out a fire started in the hotel's kitchen.

He set up the More community, where he created a philosophy based on each person's acceptance of their perfection. He managed to have More proclaimed an official university in the California system. One impediment to this was that they would have to participate in conference athletics, so Vic formed a boxing team from among his communal followers (all much older than their collegiate rivals and they eventually placed several competitors in the National Finals.

There are a number of first-person accounts of Vic having cured people of cancer. This is the kind of spin that Vic uses to set you up for an encounter with him.

By the time we got to Hawaii we felt trussed up like those little piggies that get spit-roasted for the luau. Not only had we swallowed the buildup, but in our few messages-via-telephone communications, he'd given us some startling things to think about. He had us in his pocket before we ever laid eyes on him. We had trekked to Hawaii to hire-and thereby empower-a self-described super-intelligent, bone-breaking, cancer-curing, master criminal/sexual guru to give us advice on how to live our lives.

And just in case we weren't quite softened up enough, we had to take what they call the "Hexing Course" as a final prerequisite before we could actually qualify for an Audience with the man. The Hexing Course is like a trip down Insecurity Lane. Say there's something that you know to be true deep down inside but you've devised a way to deny it. A hex is when somebody puts it back in your face. And they don't even have to be aware of you to do it. An ambitious co-worker is hexing you about your lack of ambition whether he knows you're there or not. Vic plays this game with an ease that is breathtaking. The whole five days with him could be described as one continuous hex, where he deftly exposed our self-deceptions and then, with a single finger, held us down as we tried to wriggle out of them.

Friday night he entered the room wearing a karate outfit with a black belt wrapped around his formidable middle. He had on dark sunglasses. He was the last to enter. Already in the room were Brian — always at Vic's right hand — Vic's wife, Cindy, his ex-wife, Suzie, and seven or eight other regulars who lived in the house.

This was Vic's gang and they had come to watch the old man work.

"Slash and burn, right?" he said as he settled into his chair. He waited for our response, which was not forthcoming. We knew he was referring to the agenda he had described the day before: that he would kill our egos on Good Friday and resurrect them on Easter Sunday. This being Friday, we were a little tense. "That's the reason no one can teach this course, 'cause you gotta tell the audience information they don't want to hear, that they badly don't want to hear."

Then, after a long dissertation about the Human Potential Movement of the sixties, which he referred to as the rise of the mind-fucking industry, he turned his attention to Sally. "You have pretty skin, pretty skin color. But sometime I'd like to talk to you about the moles. And about what can be done with them sensually."

"The moles …," said Sally, not sure of where this was going.

"Sensually?" I asked. "What can be done with them sensually?" I tried to sound casual, but my voice had risen a full octave.

"You see," he suddenly focused on me. "You're scared to death that somebody knows more than you do about broads and might take her away from you because she's so good. But you don't have to be afraid of that. That's one of those hexes you bought. That's what this is all about; I'm trying to erase all that garbage you guys have bought." He held up his hand. "I know more about sex than you're ever gonna find out about. I can do your wife from here. I don't know whether she wants to admit it to you or not, but she felt me on three different levels when I put up my hand just now. You understand? I have that kind of control over women."

I nodded vigorously-not so much to agree with him-I just didn't want him to kill me.

"The point being that you guys are heavily invested in this bullshit that you believe very strongly. And if you don't get rid of it in this course, you don't have any other place to get rid of it.

"Which bullshit?" I asked earnestly.

"The bullshit that you are not such a bad male chauvinist, for one."

I started wriggling immediately.

"And …. I mean you're holding on to another piece so hard, we can't go any further."

"Tell me the one I'm holding onto."

"That you're sexually inadequate."

Now I was totally lost. The room was spinning around and I had no feelings in my hands. "I'm holding on to that?"

"Very hard."

"I don't understand."

"Only some guy who was afraid that he couldn't do that well would be on the edge of his chair during this conversation."

"Well, I'm definitely on the edge of my chair."

"You are sexually adequate."

"Well, I think I am, too."

"Then why are you so up-tight?"

"I …. I'm up tight, because …"

"Give it up, man, it's because you're hexed. Just flat give it up and you're off the hook. You don't have to fight all these fights; just give it up. You got this piece of information somewhere, that if you ran into a guy who knows more about women than you do, you'd be in trouble with this beautiful wife of yours. It's a lie, man; it's a lie."

"I am afraid of that."

Then I made the fatal mistake of misting up a bit. Frankly I didn't know what else to do.

"Don't pull that, man — the Kleenex is in front of you — don't pull that. That was not a cue."

This last remark was, I believe, a reference to my profession.

Destroying my ego was a piece of cake for Vic. He went for the things I was proudest of: my ability to care for my wife, and my belief that our life and our marriage were lived equitably. And he tossed me to the mat with such ease that it actually frightened me. Every time I opened my mouth, he pointed out the arrogance in my tone. Every time I jumped in to express an opinion, he showed me how I was preempting Sally from ever expressing herself truthfully. He called me a bigot; he proclaimed I was a wife-abuser, often and forcefully, and when I argued, he effortlessly exposed my abuse to the room.

He was no easier on Sally. His point was that the two of us were in collusion with our male chauvinism. If I was "marbled through with arrogance," Sally was sitting "on a mountain of lies".

"You were sold this bill of shit," he said to her, "and a lot of people are still trying to make sales on it. The bill of shit that you were sold is that because you're a woman you're a second-class citizen. Now I know you don't really believe it, but in fact it's been drummed in so heavily that you wear it like a suit that's actually your skin. And every time you need a way out of something uncomfortable, you play the inferior card.

"You think that sometimes you have to throw the game to him, or tip over the blocks so things'll go his way, so he'll be nice to you when he comes home. But the reason he's nice to you at home is because you're the best he can find to be with. Not because you tipped over the blocks, not because you scrubbed the floors, not because you baked a cake, or any of the rest of that shit, fucked him when he wanted to get fucked. The reason he wants you at home is because that's the only way his life is worth shit. And if it's not like that, quit him and find another game to play."

Sally sat still for a long moment, chewing it over.

Vic continued, "It's a lie that you think you're inferior."

Finally, she nodded.

"Can you hear this?" he said to me. "She's telling you that she thinks she's a lot brighter than you are. She probably thinks she's a lot brighter than me, too, but she's not quite sure. But she knows she's a lot brighter than you are. And there's no equity for her not to get that billing."

Now it was my turn to chew things over. "She's a lot of things better than I am. I just don't know that brighter would be the first one on my list."

"We're not talking about your list." With that he turned back to Sally.

"Okay, you ready to tell your old man you're smarter than he is? He's hard to tell. I've beat him up some, and he's looser now, but you could have said it: that you're smarter than he is. You could've given me a hand. I'm out here all by myself, carrying your silks, the least you can do is back me up on this."

"I … I …. Y'know what, Vic …?"

"No, that won't do." He cut her off sharply. "That's how you got here: with your intense willingness to do it his way. I know you're willing to do it his way, but we're not talking about that."

"But …. I was just going to say that sometimes I think I'm a lot smarter than he is, and sometimes I think he's a lot smarter than me. That just feels like the truth to me."

He rolled his eyes. "Okay. All of us are stuck on a ledge inside the mouth of the Kilauea volcano. None of us has ever been inside there before. And it's obvious the only way we're getting out is if we're led by someone. Who would you choose to lead us? None of us has any information about living on the inside of a volcano."

"Who would I choose to lead us?"

He nodded and waited.

"Me."

"Then why do you want to argue with me?"

Sally started to laugh; Vic laughed with her. "Why in God's name do you want to argue with me?"

Her face was flushed, like she had gotten caught with her hand in the cookie jar.

"So," he said, "there are some times when you think you're brighter than he is, and there's some other times you think you're brighter than he is."

"In order for you not to be a male chauvinist" he said to me, "if that's a goal, you must run all your shit through her. And then you're still a male chauvinist, you're just not stinking, you just don't smell. Run everything through her. The goal isn't to change from being a male chauvinist. The goal is not to stink up the room with it."

We were into Saturday now. And I was dropping like a stone. On the break, we went to the beach to clear our heads, and every time I spoke Sally would look at me and nod, acknowledging a tone or an attitude that pointed up my arrogance. She was cutting me no more slack than Vic was. I gave up talking altogether. I don't remember ever feeling more desolate, more lost as to what was true and not true, as we walked along the beach in silence. I ran the scenes of our life together: our hopelessly romantic courtship, our years of struggle and growth in New York, our emergence as a publicly owned "perfect couple," our smugness as we watched nearly every other relationship in our circle cool and split apart. We were always the best couple; she was always the most loved woman. Now every scene seemed tainted with deceit, compromise, and brutishness.

When we got back into session with Vic that afternoon, I tried to surrender; I was done fighting; I was tired of losing. But he wasn't finished with me yet.

"What she wants is equity," he said. "The reason you're here is because she wants equity. There isn't any other reason."

I agreed with him completely. I told him that I had brought up that very thought in a conversation the week before, that I knew we were coming to Hawaii to deal with the inequalities in our relationship. He told me that my having to say that I had thought of it the week before is the very reason that she can't bring herself to say it now.

He asked Brian to tell a joke, the one about the farmer's prize rooster. All through Brian's telling of the story, Vic would direct him — on his tone, his timing, his comic shading — until Brian could barely think straight. They were delightful, the classic straight man and baggy-pants comic. It was clear they had been telling this joke together for years. Just before the punch line, Brian stopped in confusion.

"Wait a minute …"

"The buzzards," said Vic, "you left out the buzzards circling above."

Brian went back and inserted the crucial buzzards. Now the two of them were cracking up, as was everyone in the room. After the joke was finally told and the laughter was subsiding, Vic, smiling, asked me what I thought.

"Needs work," I said, laughing.

Suddenly, the laughter died down and I felt the whole room's attention on me.

"Just kidding," I said.

"You weren't just kidding. That's the way you live. And when you say, 'I was just kidding', you leave your wife hopeless, because you haven't seen the problem yet.

This was a pretty ornate way to call your attention to it. I mean we have done literally everything but the dance number for you, just so that you can understand that you are a bigot." His voice was rising. "You weren't just kidding. And that's exactly where she lives. Because she won't do this one-road, don't-turn, bullshit, which is the only choice you offer. Because she won't live up to that, you think she 'needs work'. And you're draggin' her to every get-well artist on the Pacific Coast. 'Work on this, willya?'

"There may be some mistakes happening in this room," boasted Vic, "but none of them are happening up here. We all have the ability to fix on an imaginary destination that we can achieve. All males have that facility, but there's another facility. And that's, from what is, to produce the appearance of more. Men can't do that. Society asks them to all the time, but men can't do that."

Our resurrection on Easter Sunday was surprisingly gentle. It happened in what I thought was a side conversation, in a break from the main event. He asked if we had any questions. It was our last day, and we were summing up. I asked Vic how I could stop my pattern of arrogance.

"Can you recommend an adjustment for me — before I take a breath — so that I don't keep saying things that keep Sally from expressing herself fully, from expressing what she really wants?"

"Just breathe, man."

"What?"

"You just did it. She sees you, man. After all I put you through for the past five days, here you are asking how to love her better. She sees that. Just breathe."

And that was it. It seemed like such a small thing after all we'd been through. But it wasn't; it was everything.

When we got back home, we walked around each other gingerly for a week or so. Sally loved me. She had her soft eyes on, but she also made it clear she had no intention of going back to what we had been before. I, on the other hand, was disconsolate over the idea that what we had been before was so irredeemably awful. Certainly there was room for improvement, but I saw no need to trash everything we had been to each other for twenty-five years. Sally kindly but firmly disagreed. She felt that the taint of our mutual male chauvinism pervaded everything, and until we admitted that fact there would be no way to go forward with any chance of real equity between us. I found myself saying very little, because I was constantly monitoring myself, for arrogance, for impatience, for expecting her to think in the same straight-line way that I do.

Then one night we had some people over for dinner and, while I was cooking, Sally started to tell a joke that was usually mine to tell. In the old days, I would have deftly taken over the performance and she would have instantly accepted. But that was the old days. I kept my nose down into my sauté pan and listened to her start the buildup to the joke. She was shaky. It was everything I could do not to interrupt her. Like Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove, I felt like my hand kept flying up uncontrollably to stop her, while my other hand kept grabbing it and forcing it down. The need to correct her was actually causing me pain, but I was determined to let her finish no matter what. Not speaking did not curtail me from being judgmental. To my taste, she told the joke terribly. It was a crime against nature. But, amazingly, when she finished, everyone laughed and clapped and patted her on the back. It was a great success. Not one person noticed that she hadn't told it my way.

"My God," I thought, "I've got to tell everyone what I've just experienced, what an incredible lesson I just learned." Then, before I commandeered the attention of the room, I said to myself — I actually heard myself speaking to myself — "Shut up, Baker. This is not your moment. Just shut the fuck up." And miraculously I did. I stirred my sauce and watched Sally work the room, which she loves so much to do. Her face was rosy and she had an ice-blue shimmer in her eyes. She was so beautiful. And I knew that if I had spoken or blurted or corrected or coached or snickered or minimized — all of which I'd wanted to do — she wouldn't be looking like this right now. So, in terms of what kind of woman I wanted to share my life with, the choice was clearly mine.

|